A man steals a car, shoots a cop, runs. A woman sells newspapers on the Champs-Élysées, dreams of New York, betrays him. He dies in the street. Nothing new. Hollywood had done it before. But not like this.

There was no plan, no blueprint. Just a borrowed script from Truffaut, a budget barely enough for film stock, and a crew making it up as they went along. The camera didn’t glide—it lurched, handheld, restless, as if trying to keep up. A tracking shot was out of the question; a wheelchair would do just fine. The streets of Paris weren’t dressed up, just there, as they were, cars honking, people passing, the city breathing.

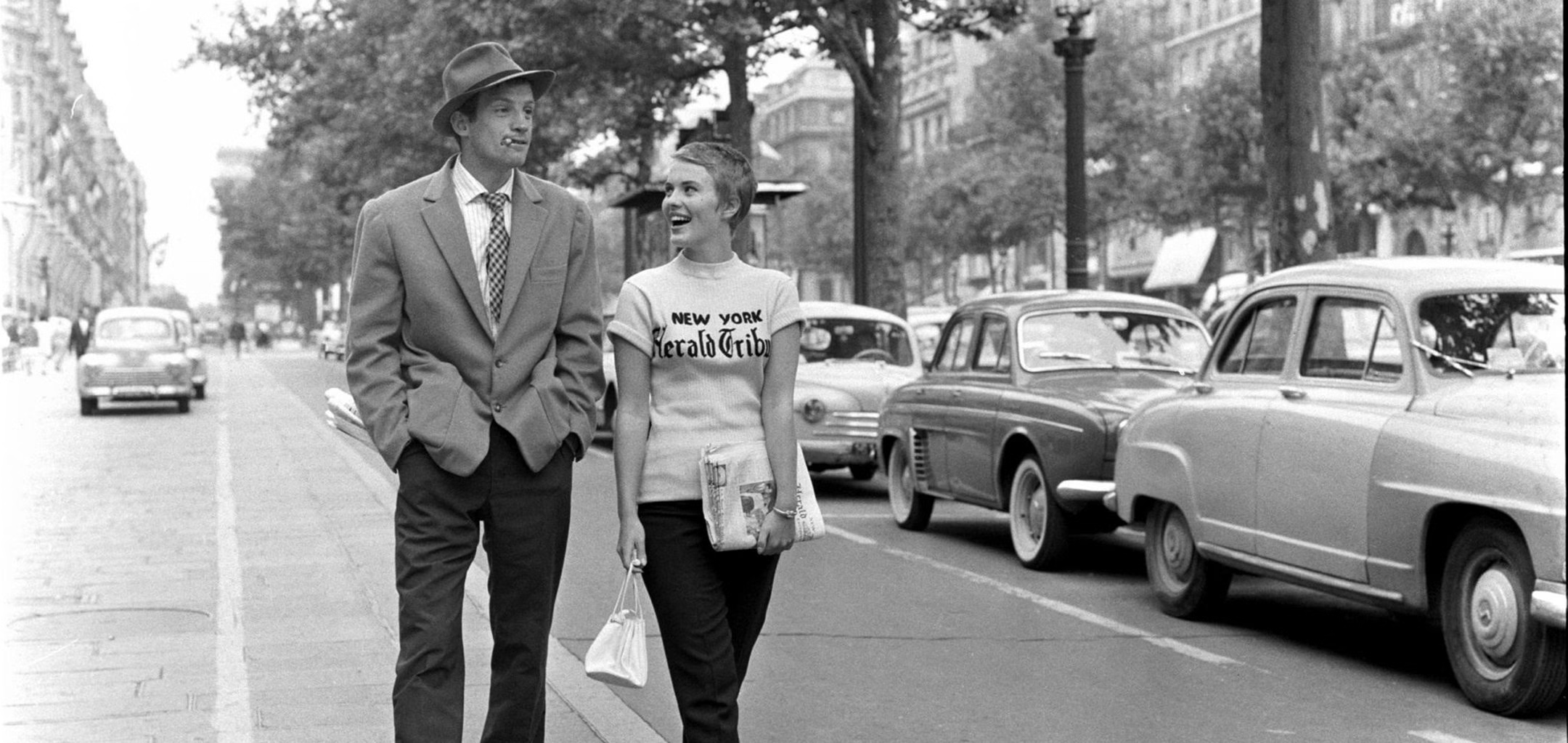

Jean-Paul Belmondo, slouched and grinning, wasn’t playing Michel Poiccard so much as existing in him. A man who speaks in stolen movie lines, smokes like he’s in a noir but knows he won’t get the noir ending. Jean Seberg, detached but luminous, was the perfect counterpoint—her Patricia was no mere femme fatale but something trickier, a character that even the film refuses to pin down. They talk, flirt, wander, talk some more. Nothing happens. Everything happens.

The film was too long. Cutting scenes was impossible—each one mattered, even when it didn’t. So Godard cut within them, slicing out frames, breaking the invisible thread of continuity. The jump cut wasn’t a stylistic choice at first, just a necessity. But necessity is where revolutions begin. When the film finally reached the screen, it didn’t just tell a story—it moved like thought.

Godard had been moving, too. From ethnology student to the Cinémathèque Française, where Langlois’ screenings were better than any classroom. From devouring films to writing about them at Cahiers du Cinéma, where he and Truffaut, Rivette, Rohmer, Chabrol tore apart the old ways, crowned Hollywood outsiders as kings, declared cinema an art of its own.

Then came Breathless. A film that shouldn’t have worked, that wasn’t even sure what it was until it was done. A film that could have been forgotten but instead changed everything.

“All you need for a movie is a gun and a girl,” Godard once said, shrugging off the film’s legacy. But he also called it his most important film, the one that began everything.

Others saw it as something more. Kurosawa called it “a film that speaks the language of the present”. Scorsese admitted, “It taught us that cinema could be reinvented, that the old rules could be thrown away.” Chantal Akerman saw in it “the first time cinema felt truly alive.”

What followed was a fracture in cinema’s foundation. The old guard scoffed; the young took notes. In Hollywood, the New Wave’s echoes could be heard in Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde, in Scorsese’s restless edits, in Altman’s loose, overlapping dialogue. Coppola, De Palma, even Spielberg and Lucas—each, in different ways, borrowed from the revolution.

In the East, new waves rose of their own—Oshima in Japan, Ray and Ghatak in India, Glauber Rocha in Brazil. The rules had been broken. Cinema no longer needed permission to be free.

Afterward, Godard didn’t slow down. Vivre sa vie, Contempt, Pierrot le Fou, Alphaville, Weekend—each one tearing apart what came before. Then, even narrative itself became a question he no longer wanted to answer.

But Breathless remains. Not as nostalgia, not as a museum piece, but as a pulse still beating in cinema today. The camera in motion, the edit that disrupts, the dialogue that doesn’t explain but simply is.

The crime film that committed the perfect crime: breaking cinema and getting away with it.

[lumiereWidget]Aarppoo Movies[/lumiereWidget]